History of Buenos Aires

Discover the history of Buenos Aires from the arrival of the Spanish explorers through to the modern-day city.

The city that was founded twice

Before the arrival of the Spaniards, the banks of the River Plate were populated by hunter-gatherer villages. When the first Spaniard, Juan Díaz de Solís, arrived, the area was inhabited by the Querandí Indigenous group. This name meant "men of fat", and was given to them by their neighbours, the Guaraní, because the Querandí fed almost exclusively on meat.

In 1516, Juan Díaz de Solís landed in the area and named the immense delta the "Solis River" and also "Mar Dulce" (Sweet Sea). His adventure ended later that same year when he and some other members of his crew were killed by members of the Guaraní Indigenous group.

On February 3, 1536, another Spaniard, Pedro de Mendoza, who had been sent by the king of Spain to stop the advance of the Portuguese, ordered the construction of a fort called "Santa María de los Buenos Aires" on the right bank of the River Plate.

The fort survived for 5 turbulent years. However, a lack of resources and the hostility of the Querandí people prevented the region from being colonized and the Spaniards left Buenos Aires and moved to the city of Asunción. The area was then abandoned for several decades.

The need to use the Atlantic as an access point for the riches of Peru and its geographical influence saw the Spanish crown send Juan de Garay on a mission to found a city and colonize the southern territories.

On June 11 1580, Juan de Garay founded the city's 2nd incarnation, known as "de la Santísima Trinidad", in the port of Santa María. He was killed 3 years later by members of the Querandí community.

For that reason, Buenos Aires is the city that was founded twice: once by Pedro de Mendoza, and again by Juan de Garay.

The trade ban issued by the Viceroy of Peru on Buenos Aires led many of its inhabitants to engage in smuggling. In this period, Castile, Spain, and Portugal were united under the crown and numerous Portuguese people arrived in the city, mainly dedicated to smuggling the silver of Potosi.

In 1592 the Adelantado came to an end and the city came under the control of the governor of Asunción.

In 1603, to put an end to smuggling, all Portuguese people were expelled.

In 1640, Portugal became independent from Spain and founded Colonia de Sacramento on the left bank of the Río de la Plata. For more than a century this place was the main hub of smuggling in the region, which was mainly carried out by the English.

The governor of Buenos Aires organised an army to put an end to the activities of the colony and, although he defeated the Portuguese, the victory had little effect on smuggling.

The 18th century and the expansion of Buenos Aires

By the time of the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht between Spain and England, the English obtained a license to bring African slaves through the port of Buenos Aires which, together with the growing Spanish interest in the Atlantic, turned the city into a regional center of trade and the natural gateway to Chile and Peru.

Its commercial importance was such that in 1776 the Spanish King Carlos III created the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata and Buenos Aires, ceasing to depend on the Viceroyalty of Peru.

Since its creation, Buenos Aires has suffered numerous invasions by English corsairs, French troops, and even Danish pirates, but the city has successfully defended itself.

In 1806 it fell into English hands although they were expelled by an army from Montevideo in the "Battle of the Reconquest". A year later the English made another attempt and were again defeated in the "Battle of the Defence".

The wealth from growing trade and the participation in the reconquest and defence of the city increased the people of Buenos Aires' feeling of pride and sympathy for the independence cause. This began a process that would culminate in self-rule.

The 19th century and Independence

Taking advantage of the power vacuum that occurred in Spain after Napoleon's invasion, on May 25, 1810, the Council of Buenos Aires declared independence.

On July 9, 1816, other provinces of the Viceroyalty followed suit and declared themselves independent from Spain. This led to the creation of the "United Provinces of the River Plate".

From the beginning, the hegemony of Buenos Aires was poorly accepted by the rest of the provinces of the Viceroyalty and disputes between them caused the provinces of Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia to create their own countries.

From 1820 to 1862, Buenos Aires saw a struggle between federalists and unitarians. The provinces of the interior of Argentina, always suspicious of Buenos Aires, forced the city to be just one more provincial capital.

However, from 1820 onwards Buenos Aires also entered a period of great economic prosperity. This was based on the livestock sector, meat salting plants, and leather exports. This period was interrupted by the war with Brazil.

The confrontations between unionists and federalists in Buenos Aires came to a halt when Juan Manuel de Rosas assumed power in 1829. He created the infamous "mazorca", a political police force that would help to shape the political future of Argentina, and the city was ruled by terror from 1840 to 1842.

When Rosas fell, the struggle between Buenos Aires and the other provinces intensified. In 1841, Buenos Aires separated from the Union in protest against the governor of the Entre Ríos province, Justo José de Urquiza, who wanted independence. In 1862 it became the capital of the unified nation.

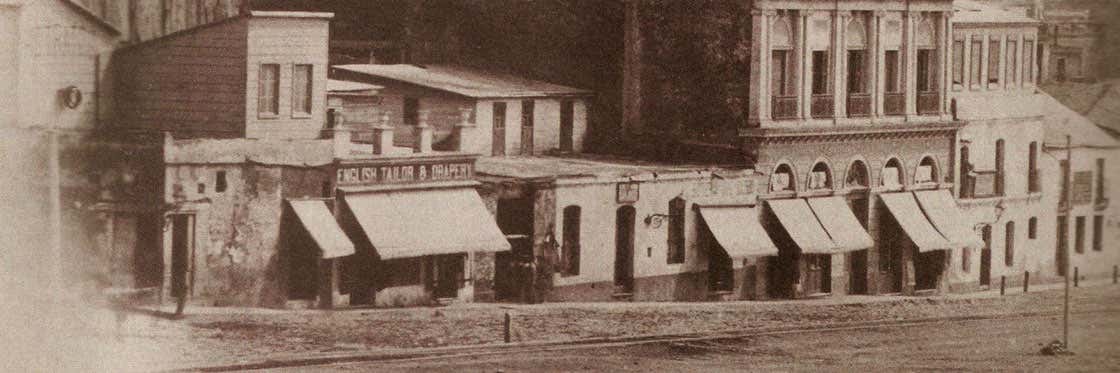

From 1864 to 1914, the population of the city multiplied by 8 due to large-scale immigration, giving rise to great changes in its appearance. Influenced by the Parisian 'Hausmann' style of the Second Empire, large avenues, squares, public buildings, and important monuments were built.

The objective was to make Buenos Aires the "Paris of South America". In 1875 Palermo Park was built and a year later the Hippodrome opened. In 1882 the construction of Puerto Madero began, in 1906 the Congress Palace was inaugurated and in 1908 the Colon Theatre.

Immigration

The history of Buenos Aires can only be understood when the phenomenon of immigration is also considered.

From 1587, when the first Black slaves arrived in Buenos Aires, the country's Black population increased considerably and became almost half of the Argentine population.

The share of the population that was of African descent later plummeted in Argentina due to deliberate political actions, such as sending Black Argentines to the front lines of war. When yellow fever swept through Buenos Aires, the army even surrounded Black communities to prevent them from leaving.

From the 18th century onwards, free trade pushed Buenos Aires into a period of great growth. The city received a huge wave of immigration, mainly Spanish, and reached 50,000 inhabitants.

In 1836 it had 62,000 inhabitants, and in 1880 this grew to 313,000. The Spanish were joined by Italians, the French, and other Europeans. Those in power at the time welcomed European immigration with an enthusiasm that contrasted with their efforts to stamp out the trace of people of African or Indigenous descent and gauchos.

It is mainly after the enactment of the Avellaneda Act of 1876 that immigration reached its peak. Immigrant hotels and the famous "conventillos", rickety rental housing for newcomers, were created. Poverty, lack of hygiene, and overcrowding led to epidemics in 1852, 1858 and 1870. The worst of these was the yellow fever of 1871.

Millions of immigrants, nostalgia for the homeland, the loss of roots, exploitation, the disappearance of the gaucho world, poverty, upheaval, prostitution, and delinquency, all merged together in the suburbs of the city. This saw the birth of the expression "el lunfardo" and a way of life from which tango would emerge.

20th century and Buenos Aires today

By the city's centennial in 1910, Buenos Aires was already the largest city in Latin America.

The city had an intense experience with the anarchist movements of the early 20th century and had its own "tragic week" when more than 700 demonstrators killed.

After years of splendour, the poverty caused by two world wars forced many inhabitants of neighbouring countries and the Argentine provinces to emigrate to Buenos Aires. As a result, the city's population tripled.

Following a military revolution in 1943, Juan Domingo Perón came to power in 1946. Perón is a notable historic figure due to his populist policies and grand reforms, but also due to his famous wife Eva Perón.

"Evita" became the icon of the regime and her premature death on July 26 1952, when she was only 33 years old, would immortalise her forever in the eyes of the Argentine people.

In 1955 Buenos Aires suffered a bombing carried out by its own military. It also experienced armed conflicts in 1962 and 1963.

A military coup deposed President Perón who was forced into exile in Spain. In 1973 he returned to power but died shortly after, which saw the military take over again.

The 1970s were dominated by the military and their expeditious policy, the montoneros guerrilla group, the disappeared, torture, and the mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. The instability resulted in great political corruption and with money siphoned abroad.

In the 1990s Buenos Aires experienced demonstrations and civil disorder.

On September 30 2009, UNESCO declared tango part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

In 2010 the city's bicentennial was celebrated and the Colon Theatre was reopened.

Today, Buenos Aires is a modern and cosmopolitan capital city that captures the hearts of all first-time visitors with its numerous tourist attractions, exciting nightlife, and inherent tango traditions.